Inspiration & Sources & References

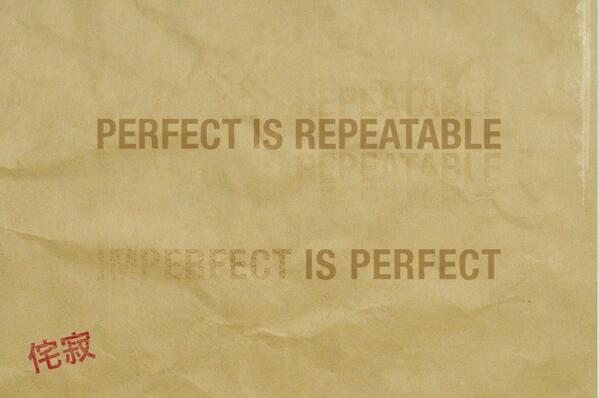

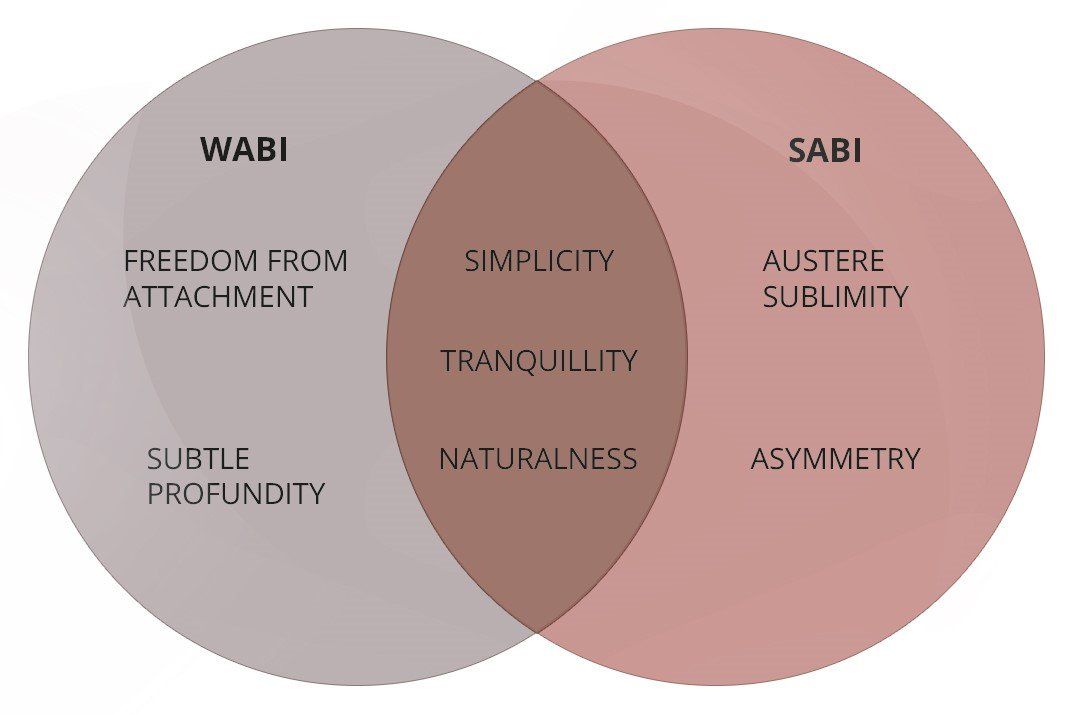

Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-Sabi is the quintessential Japanese aesthetic. It is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional. Characteristics of the wabi-sabi aesthetic include asymmetry, asperity (roughness or irregularity), simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy and appreciation of the ingenuous integrity of natural objects and processes. „Pared down to its barest essence, wabi-sabi is the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection and profundity in nature, of accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay, and death. It's simple, slow, and uncluttered-and it reveres authenticity above all. Wabi-sabi is flea markets, not warehouse stores; aged wood, not Pergo; rice paper, not glass. It celebrates cracks and crevices and all the other marks that time, weather, and loving use leave behind. It reminds us that we are all but transient beings on this planet-that our bodies as well as the material world around us are in the process of returning to the dust from which we came. Through wabi-sabi, we learn to embrace liver spots, rust, and frayed edges, and the march of time they represent. Wabi-sabi's roots lie in Zen Buddhism, which was brought from China to Japan by Eisai, a twelfth-century monk.” -architect Tadao Ando

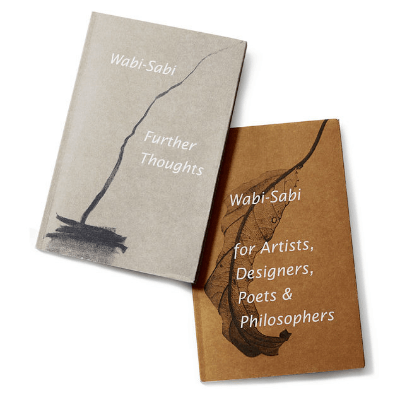

Leonard Koren's latest book is called Wabi-Sabi, Further Thoughts. It is an extension of his influential 1994 classic on the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers.

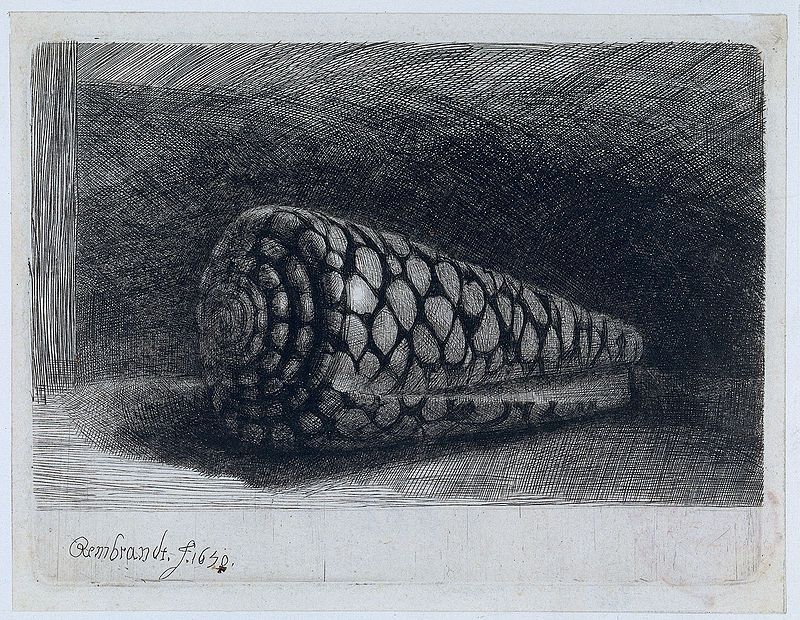

Conus Marmoreus is a 1650 etching by Rembrandt

of a conus marmoreus in his collection.

It is now in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

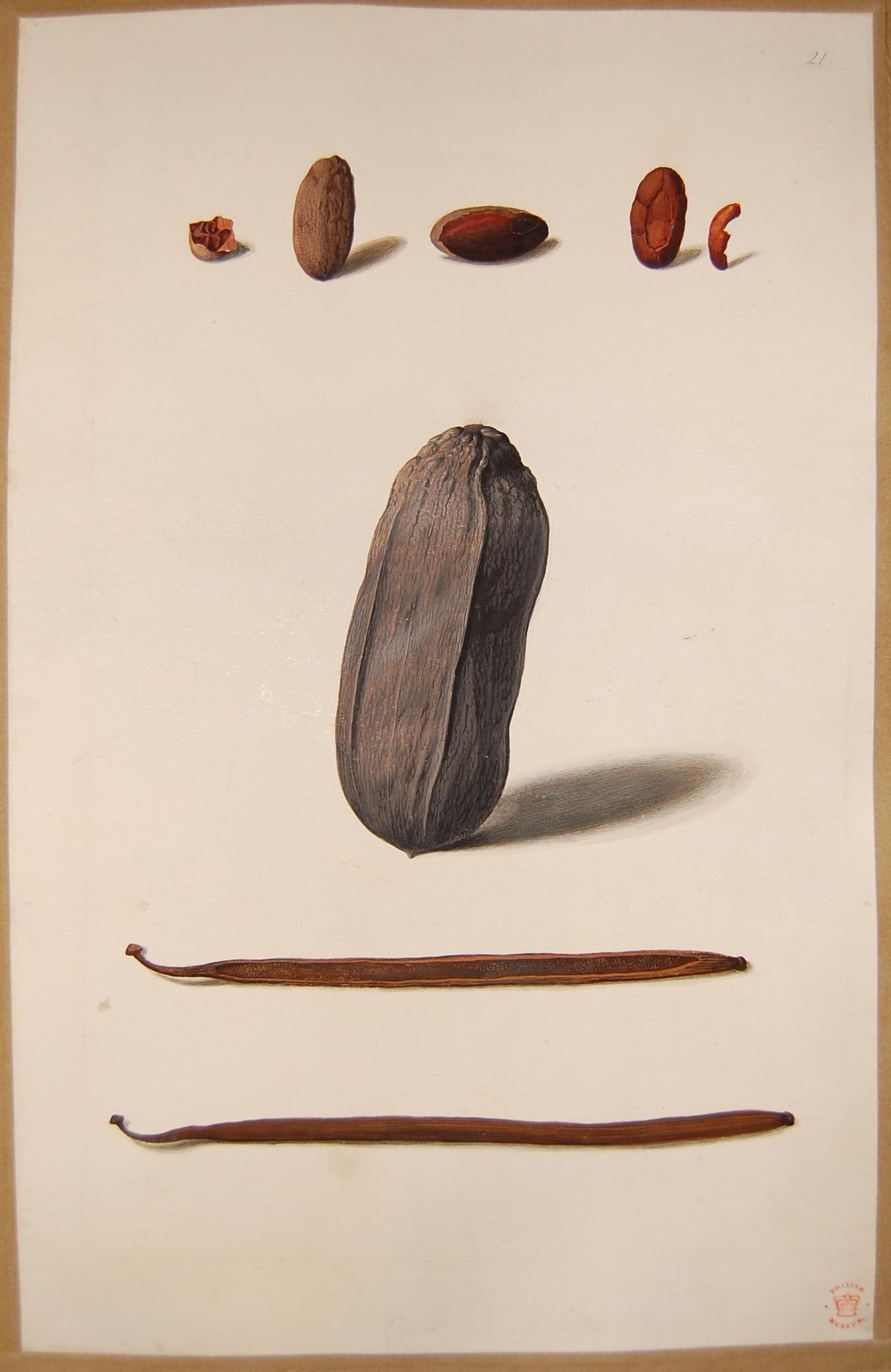

Studies of vanilla beans and pods,

drawn by Nicolas Robert (1614–1685)

The British Museum

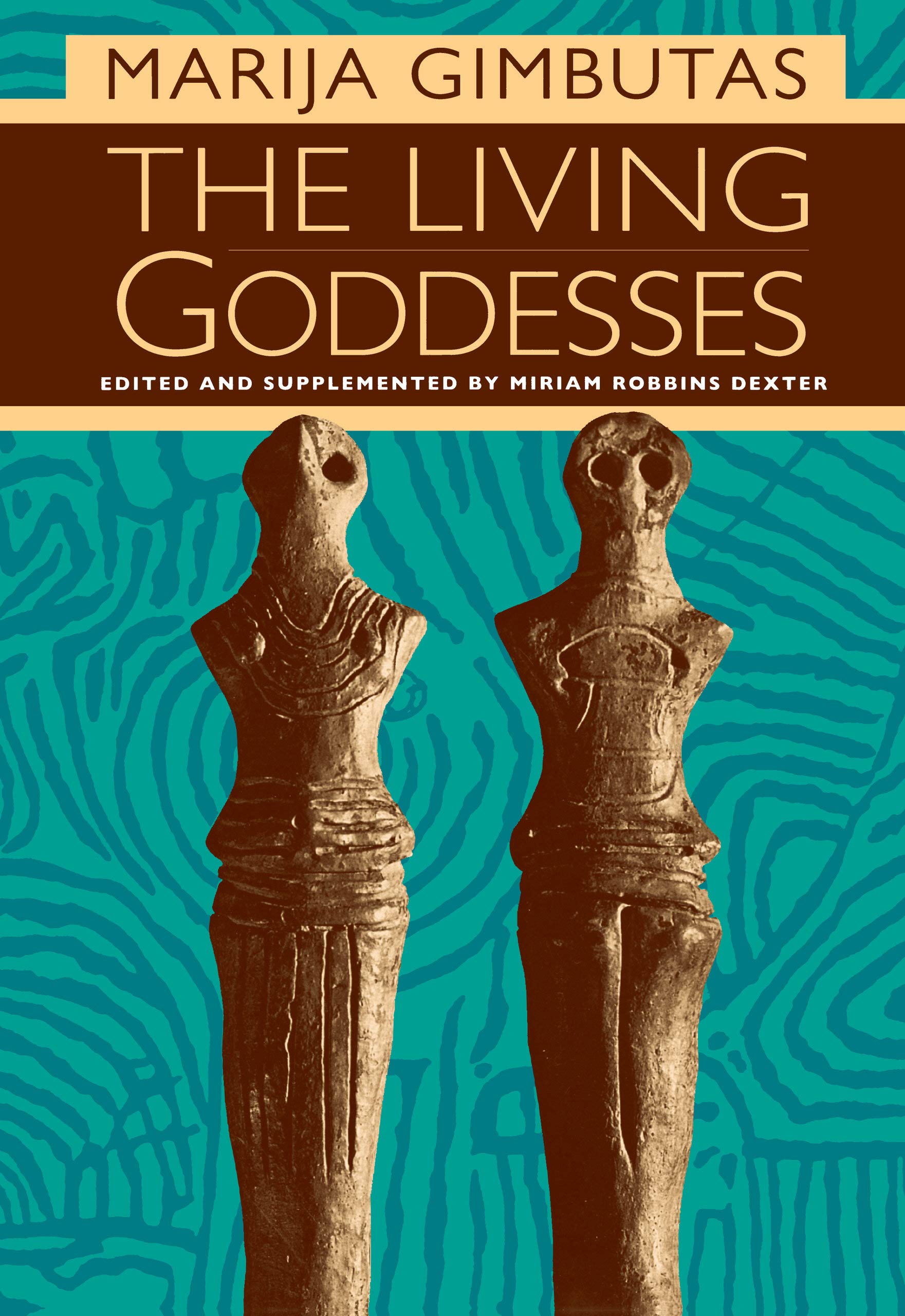

The Living Goddesses crowns a lifetime of innovative, influential work by one of the twentieth-century's most remarkable scholars. Marija Gimbutas wrote and taught with rare clarity in her original-and originally shocking-interpretation of prehistoric European civilization. Gimbutas flew in the face of contemporary archaeology when she reconstructed goddess-centered cultures that predated historic patriarchal cultures by many thousands of years.

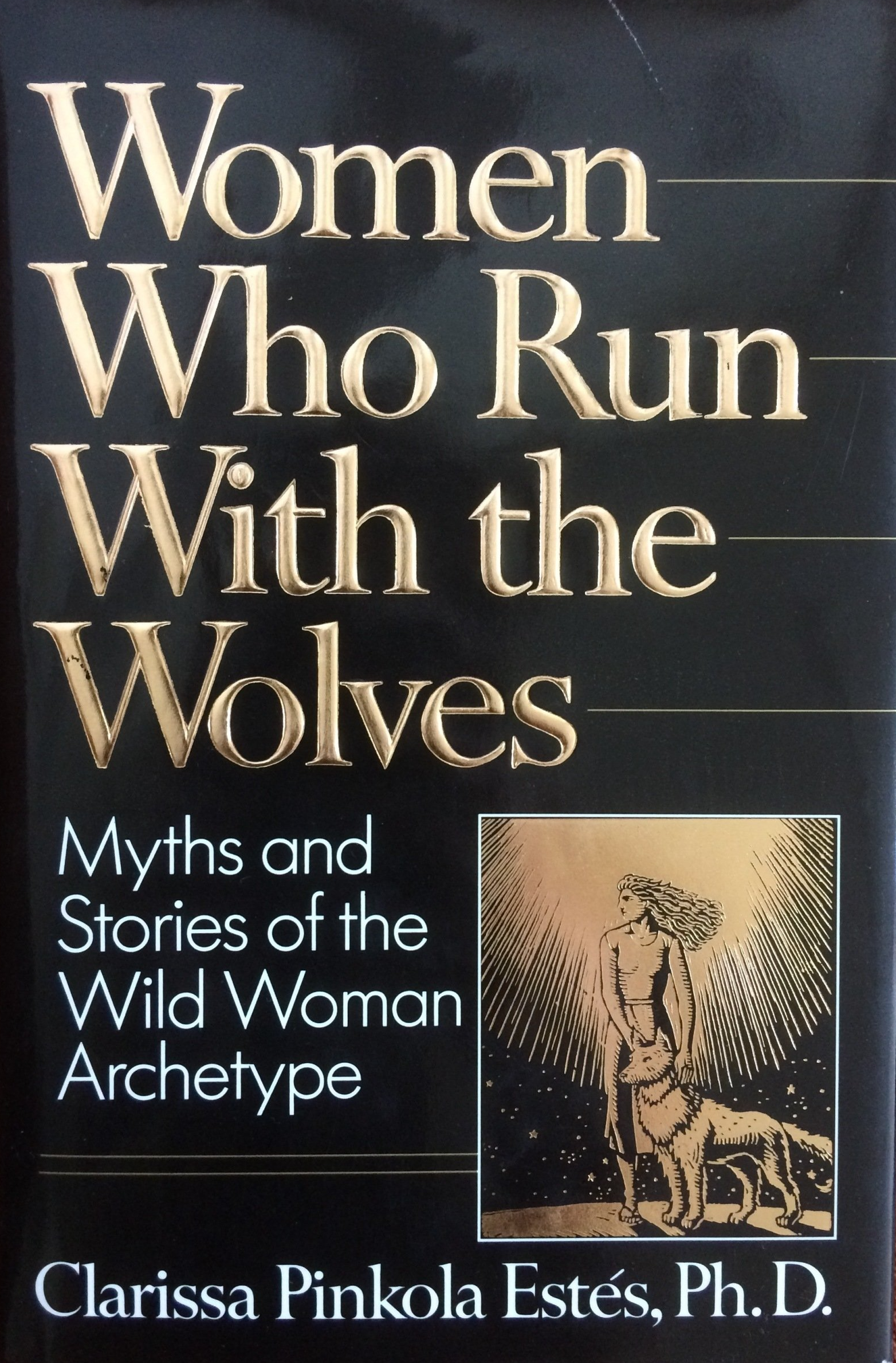

A book by Jungian analyst, author and poet Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Ph.D. She unfolds rich intercultural myths, fairy tales, folk tales, and stories, many from her own traditions, in order to help women reconnect with the fierce, healthy, visionary attributes of this instinctual nature.

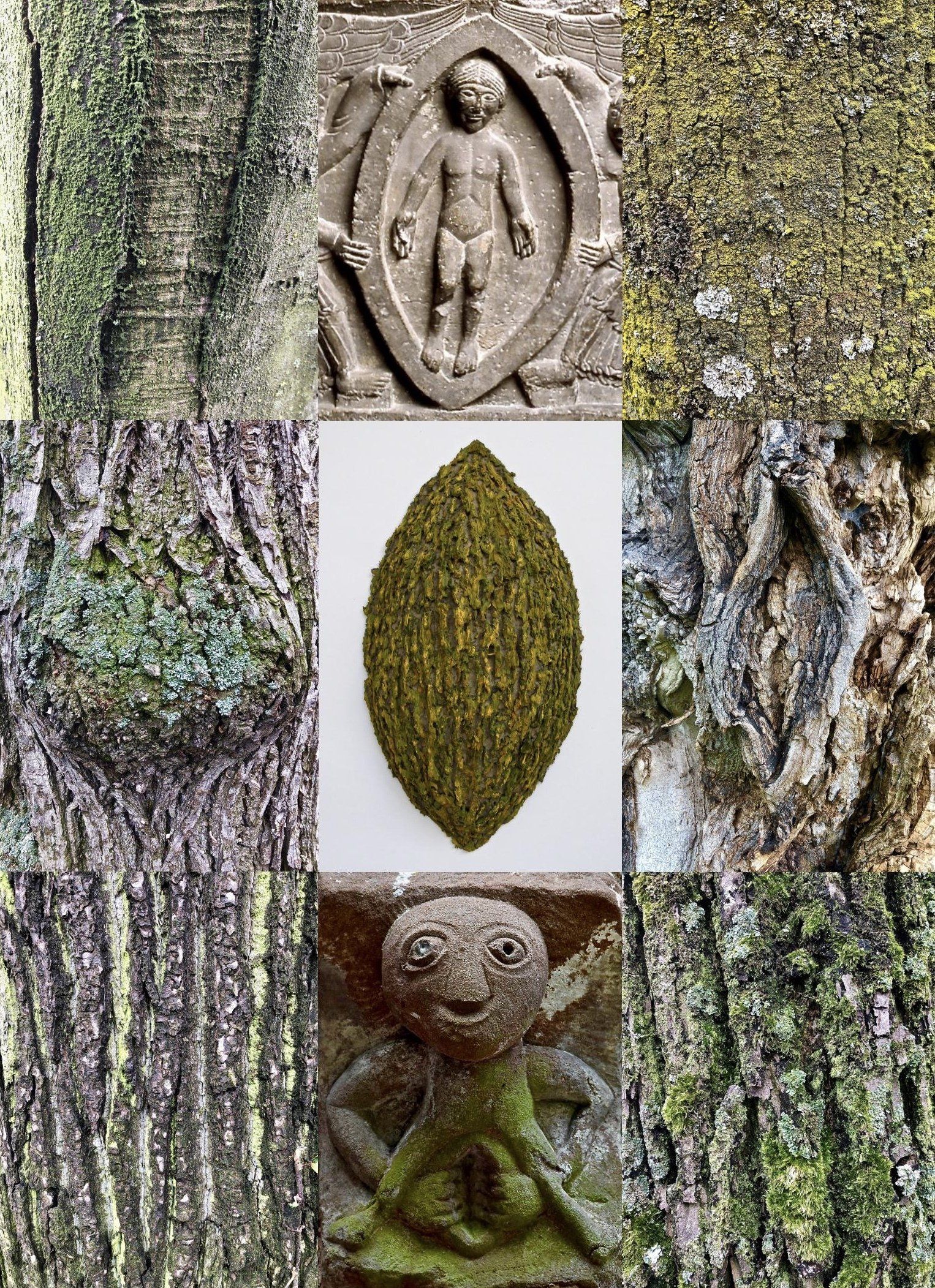

Sheela

Sheela are figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. They are architectural found on churches, castles and other buildings, particularly in Ireland and Great Britain. By opening her vulva as wide as possible, this figure seems to show us where we come from and, perhaps, to invite us back into her womb once life comes to an end.

Sarcophagus of the Infanta Doña Sancha

In the centre, the soul of the dead is shown by two angels within a mandorla, an image of salvation, but also a universal symbol of the Goddess and the Yoni.

Created c. 1100 by an unknown master, Church of San Salvador and San Gines in Jaca, Huesca, Spain

Venus Impudique ("Immodest Venus")

Mammoth ivory, ~16 000 BC

It was discovered in 1864 by the Marquis Paul de Vibraye at Laugerie Basse. It was the first Venus figure found in France.

Cycladic figurine

2700-2300 BC

The Cycladic civilization flourished on the islands of the central Aegean during the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC). Sculptures in marble are the most characteristic products of the Early Cycladic civilization.

The meaning and function of Cycladic figurines is kind of an enigma. In the absence of written records, any interpretation has to be based exclusively upon archaeological finds and reasonable assumptions.

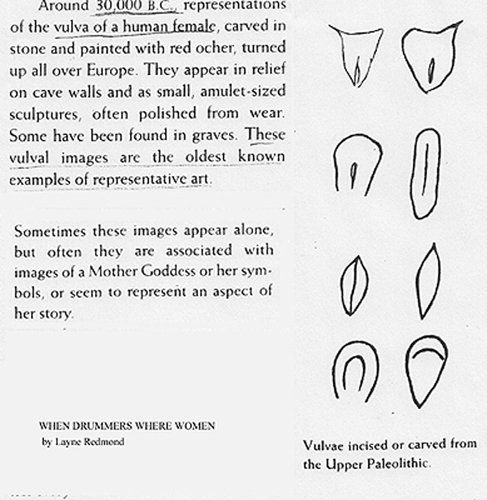

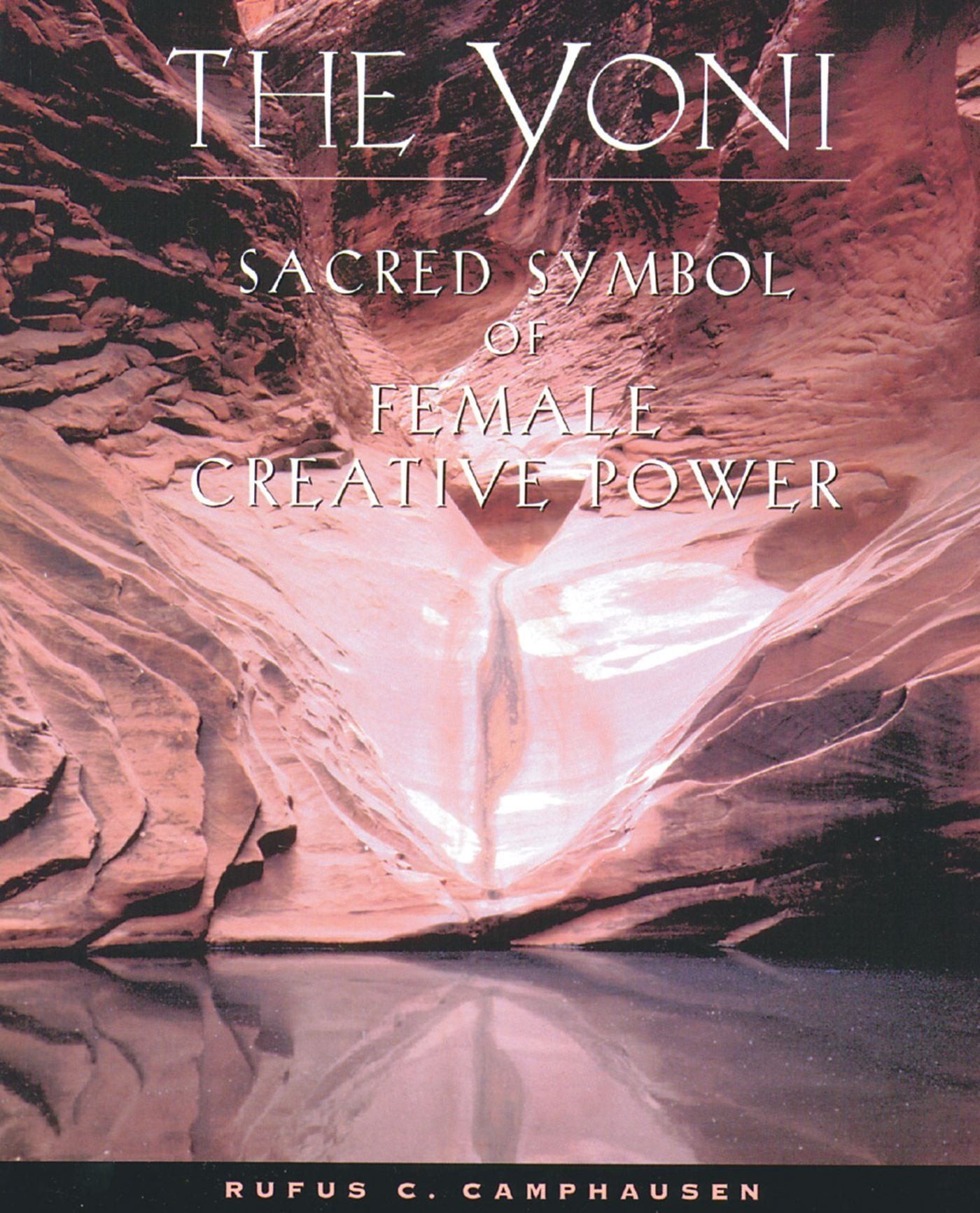

From earliest times, humanity has found visual expression for the cosmic forces of creation, birth, and passion in artistic representations of human genitalia. Fertility cults centered on phallic worship are well documented, but older and even more pervasive are Goddess images of the vulva-known in the East since ancient times as the yoni. Yoni symbolism is a part of spiritual traditions in every part of the globe-from naturally occuring rock formations revered by North American Native peoples to the shakta-pithas of Hindu temples, and from early Celtic sheela-na-gig carvings to the Japanese kagura ritual.

The Yoni traces this primal motif in Australian Aboriginal folk tales, in alchemy, in Tantric practices, and in contemporary art by painters such as Georgia O'Keefe and Judy Chicago.

Dozens of illustrations, many in color, reproduce the variety of carvings, drawings, and other portrayals of this universal symbol of feminine creativity.

The evolution of the female image in 40,000 years of global Venus Art

1. This book is the first pioneering study of global ‘Venuses’ who are part of an ancient and contemporary art traditionally called ‘Venus Art’, the art of the primal mother(s), the art of the female ancestors.

2. Venus Art reflects the consciousness of egalitarian societies of peace in which women and feminine values play or have played a central role, in which MA or the MATER or MOTHER and the primal mothers of the clan are central.

3. To date Venus Art has been misunderstood, neglected and not integrally researched. The art has become eroticised and sexualised. The purpose of this book is to rehabilitate Venus Art. Venus is no pin-up or sex idol. She is a manifestation of the divine Mother MA.